WHY EXPLAIN THE OBVIOUS?

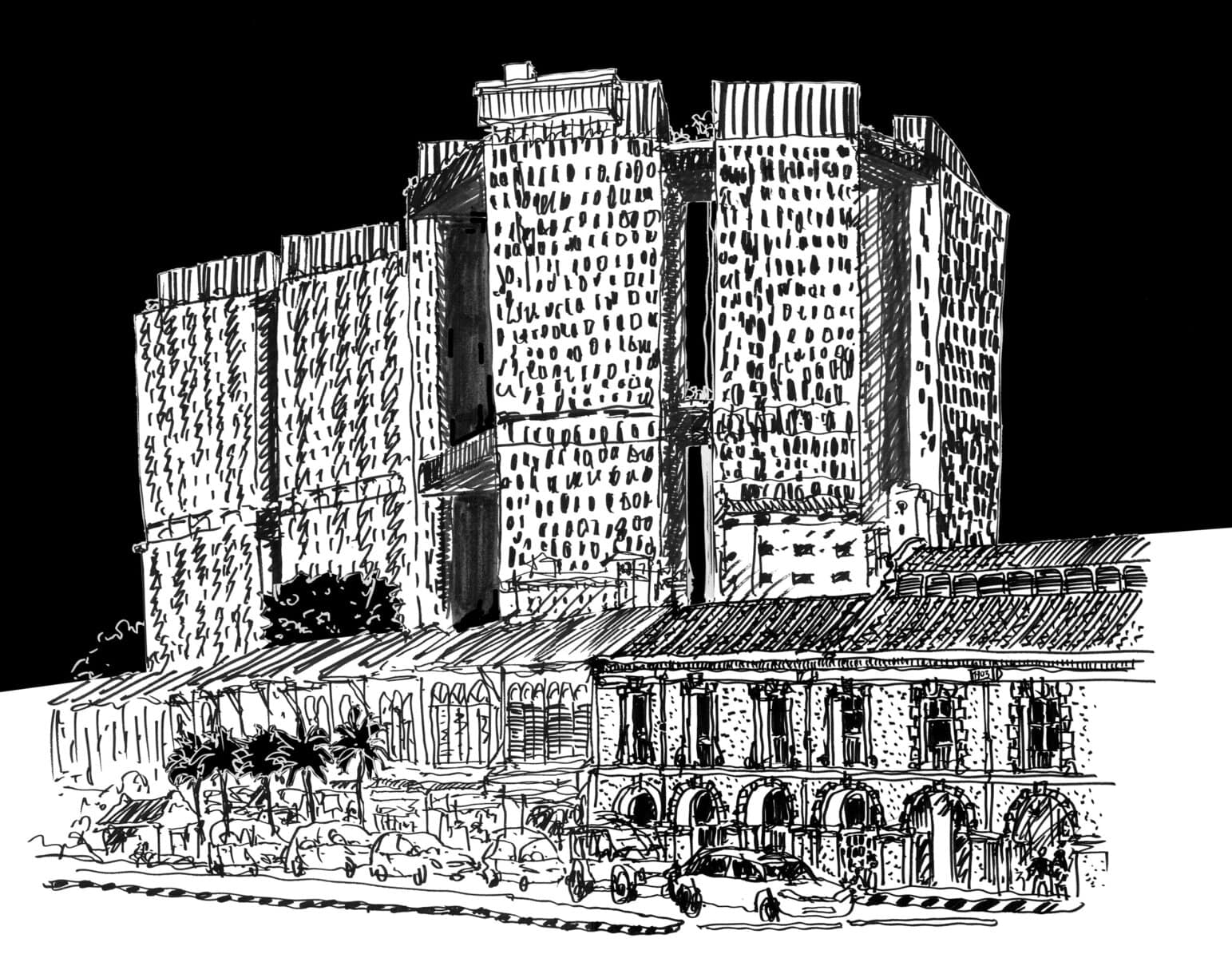

One of the strongest impressions a visitor takes away from Singapore, beyond cleanliness, safety, and order, is its extraordinary ease of use.

This quality is not the result of form or material alone.

It is the result of something less visible, yet equally architectural: clarity.

Singapore demonstrates that architecture is not built only with concrete and steel, but also with words, instructions, signals, and decisions that explain how space is meant to be used. In a city of nearly six million people, this layer is not optional. It is fundamental.

One might object that it is easier to manage a single city than an entire country, where different administrations make different decisions. That is true. Yet this reinforces the point: Singapore demonstrates a strong alignment among the city, its population, administration, and design. Design is not the exclusive act of architects; it is the cumulative result of many actors, from institutions to everyday users.

Singapore is not simply a “city in a garden” (which would already be an achievement). It is an intuitive city. And intuition does not come easily: it is designed.

This is evident from the first encounter, often at the airport, where facilitation systems were implemented long before they became standard elsewhere. Despite its Asian cultural identity, the city rarely feels overwhelming. It is clear, readable, and legible almost immediately.

This clarity is not accidental. It is intentional.

Despite having four official languages, Singapore rarely feels confusing. Wayfinding is consistent, information is redundant, and decisions are anticipated before they become stressful. This is not merely the result of good signage, but of a deeper principle: Singapore explains the obvious.

This logic is particularly evident in the subway system. For newcomers, the network may initially appear complex, with unfamiliar station names, multiple lines, colour codes, and multilingual signage. Yet the system quickly reveals its intelligence.

At major interchange stations, where two lines cross, transfers follow the most frequent passenger flows. Doors often open directly opposite each other. No change of platform is required. No guesswork is involved. The system anticipates where you are likely to go and places the answer directly in front of you.

This logic extends further. Many shopping malls are integrated with major metro stations, and several malls are connected underground, forming continuous pedestrian networks such as the well-known “link” systems. These environments require highly sophisticated orientation strategies, yet they feel natural rather than forced. The city does not ask you to solve the problem.

It solves it first.

This approach extends far beyond transportation. Singapore consistently reduces cognitive load by guiding behaviour through clarity. Instructions are explicit. Paths are unambiguous. Rules are visible. The result is a city that flows, not because people are controlled, but because friction has been removed.

To some Western observers, this can feel excessive. Over-guided. Even authoritarian. The sensation of being constantly instructed can be interpreted as a loss of freedom.

Lived experience, however, suggests the opposite.

By explaining the obvious, Singapore removes uncertainty. Removing uncertainty empowers individuals to move confidently, safely, and independently. In contexts where private space is limited and most life unfolds in shared environments, this clarity fosters a strong civic attitude—one that begins at the doorstep.

Civic responsibility does not emerge through enforcement, but through shared understanding. When systems are clear, people trust them. When people trust systems, they participate rather than resist.

The Lesson

Good design does not display intelligence.

It eliminates the need to consider what should already be obvious.

In architecture and urban systems, complexity is often mistaken for sophistication. Yet clarity is the more demanding task. Anticipating behaviour, eliminating doubt, and making the right choice self-evident requires deep understanding—not simplification.

This aligns directly with Less Is Bold: clarity requires courage. Clear decisions produce aware users.

Explaining the obvious is not paternalism.

It is care.

It is education.

It is a responsibility.

In cities, care enables millions of individuals to coexist, move freely, and live together without friction. This is one of Singapore’s most valuable lessons: architecture and design are not only about creating space, but about guiding life gently, clearly, and responsibly.