DESIGN IS A CONDITION OF LIFE

Architecture is often discussed as a choice: a profession, a discipline, a cultural expression. Yet one of the most radical insights to emerge from contemporary architectural discourse is precisely the opposite.

Architecture is not optional.

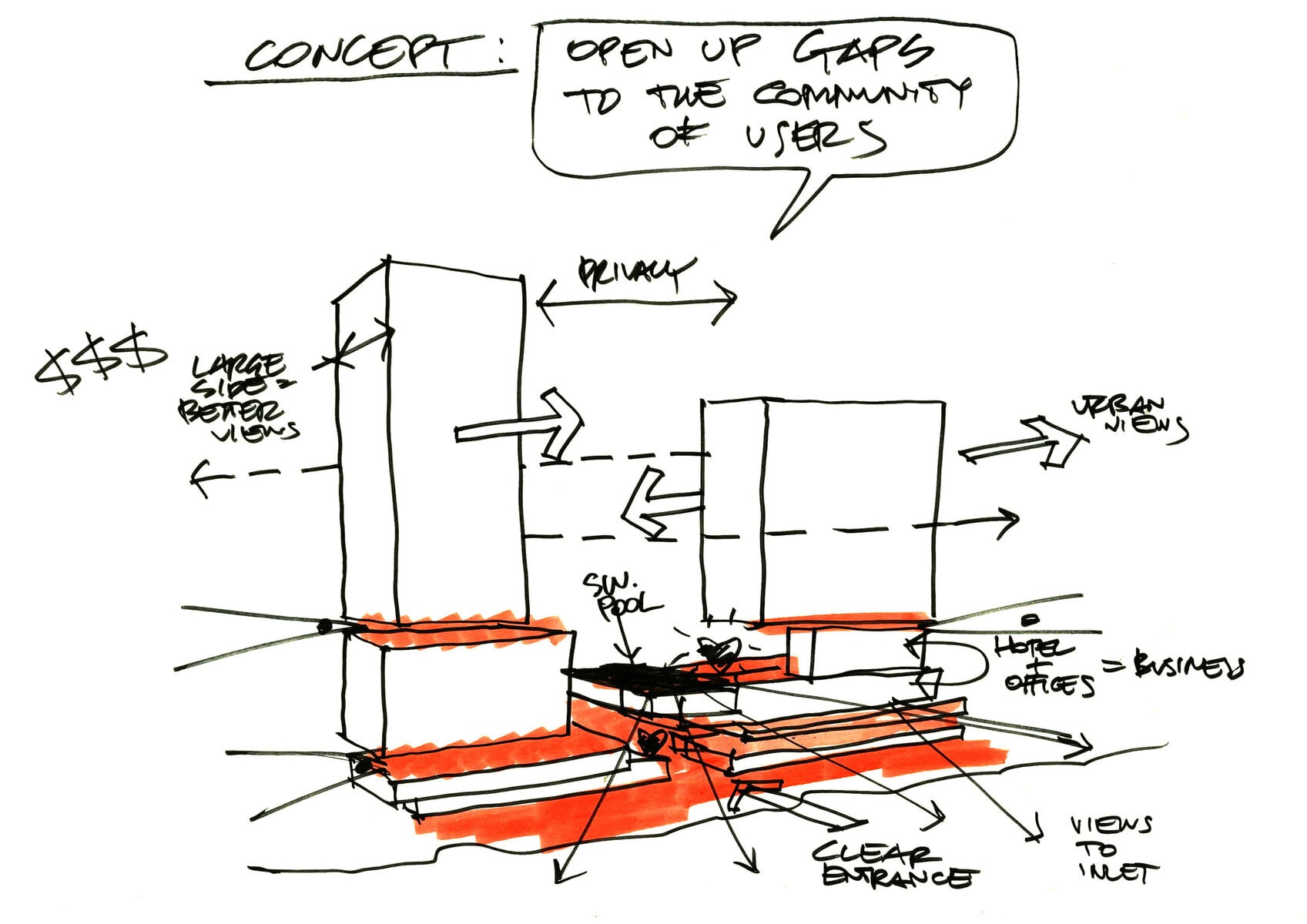

This idea surfaced during a design workshop at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), where a presentation on architectural design process prompted an unexpected conversation. Among the audience was a philosopher teaching at the institute, whose background lay outside architecture but deeply within questions of meaning and human condition.

After the lecture, he offered a simple but unsettling observation:

Architecture is inevitable.

At first, the statement appeared abstract. Clarification followed.

One can choose to watch a film or not.

To read a book or ignore it.

To enter a restaurant or walk past it.

But one cannot choose not to engage with architecture.

Human life unfolds entirely within built space. We are born and die in hospitals. We grow up in houses. We study in schools, work in offices, move through stations, gather in public spaces, and recover in care facilities. Every stage of life is spatially framed.

Architecture is not a backdrop.

It is a condition.

This perspective reframes architectural responsibility entirely. If architecture is unavoidable, then its impact is continuous and cumulative. It influences behaviour, perception, interaction, comfort, exclusion, dignity, and belonging, whether intentionally designed or not.

In this light, architecture is not merely about producing form, responding to fashion, or generating visual impact. Nor is it reducible to technical performance alone. Its most profound dimension lies in meaning: how space communicates values, priorities, and assumptions about life.

The observation also exposed a broader issue in architectural education. When architecture is taught primarily through trends, aesthetics, or technical optimisation, it risks neglecting its deeper inevitability. Students learn how to impress, but not necessarily how to care. They learn how to produce effect, but not how to understand consequence.

Recognising architecture as inevitable changes the order of thinking.

If architecture cannot be avoided, then design is not neutral.

If design is not neutral, then intention matters.

If intention matters, then concept must precede form.

This realisation crystallised into a guiding principle:

Concept first.

Form follows.

Meaning lasts.

In a world increasingly shaped by speed, image, and consumption, the inevitability of architecture becomes a call for clarity. It reminds designers that every decision, even the smallest, participates in shaping human experience.

Design, in this sense, is not simply a professional act.

It is an ethical one.

And if architecture is inevitable, then thinking deeply about it is not optional, it is a responsibility.